|

||||

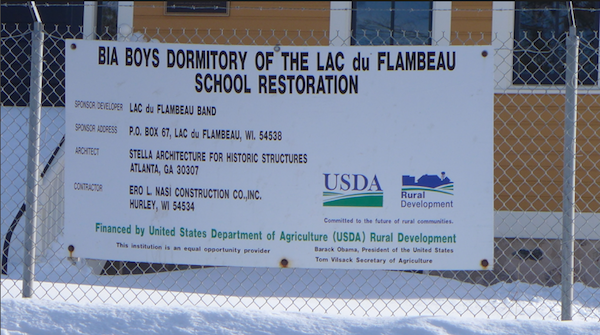

The Situation of Wisconsin Tribes TodayRepatriation, Decolonization, Interventions, Sovereignty Acts and Survivance During the twenty-first century, Wisconsin Indian nations, like Native American communities elsewhere in the country, and like indigenous peoples in various parts of the world, have taken decisive steps to "decolonize" their cultures and self images. For Lac du Flambeau Ojibwe, this canoe project was part of this process, seeking to replace images of Ojibwe traditional arts as "lost heritage of the past" and of Native American cultures as "disappearing" or "dying," and replacing such portrayals with a celebration of the dynamic, evolving nature of contemporary Ojibwe life today. Where the dominant society of the United States developed images of the "Indian" that suited state agendas of disenfranchisement and assimilation, contemporary Native activists seek to create new, Native-centered images that will help galvanize their communities to celebrate and maintain their cultures in the future. Such work involves in part selecting elements of tradition to adapt and repatriate into contemporary life in new ways. The production of birchbark canoes in a contemporary context for use in new ways in a university residence hall or in a school program—as discussed in the EDUCATION page of this website—can be seen as an instance of what White Earth Ojibwe scholar Gerald Vizenor calls "cultural survivance," the creative and dynamic way in which modern Native Americans carry their cultures forward, not as relics of the past, but as instantiations of the present and future. "Repatriation" is a term of great importance in much contemporary Native American activism. In 1990, the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act required organizations that receive federal funding to return to Native American communities cultural items—human remains, sacred objects, other pieces of material culture—that were acquired from Native communities in the past. Museums, universities, and state historical societies began a long and sometimes complicated process of determining which items needed to be returned to which nations and in what ways. Sometimes, Native leaders have allowed objects to remain in the possession of museums or other institutions, but have asked that they be kept off exhibit. Sometimes repatriation can raise issues within Native communities, as tribal members may disagree about what items of past culture should be repatriated and how. Robin Ridington and Dennis Hastings (In'aska) have explored such issues in their study of the repatriation of sacred objects of the Omaha people. Another element of repatriation is the return of verbal traditions, or traditional knowledge and actvities, and the reactivization of such items in the cultural life of an Indian nation. The canoe project is a good example of such repatriation: often elements of canoe making techniques have been preserved in archival materials or films, as detailed in the TRADITION page of this website. Artists consult such sites to see how their ancestors practiced an art and to compare the depicted traditions with the practices that they have devised or learned in the present. The detailed CONSTRUCTION page of this website is potentially a useful resource for persons who would like to learn birchbark canoe building in the way that Wayne practiced it in the fall of 2013. The goal is not to create a canoe as a symbol of the past, but to re-establish canoe-making as a vibrant and meaningful activity in the present. The canoe project can be compared to other acts of knowledge or cultural repatriation going on in other Wisconsin Indian nations in 2013. On the Lac du Flambeau reservation, Wayne has been involved in an annual event called the "Ojibweg Winter Games," which seeks to reacquaint Ojibwe youth with once suppressed traditional games and sports. Among Ho-Chunk people, the nation has worked to re-establish a buffalo herd on tribal lands, cooperating with the Intertribal Bison Cooperative, which to date has aided some 57 tribes in 19 states to re-establish buffalo herds. You can read an article about the Ho-Chunk nation's Muscoda Bison Prairie 1 Ranch HERE. As noted in the discussion of Native American diet in the South Quadrant of this website, the reintroduction of Native foods like buffalo meat can also serve to reverse the negative health effects of generations of poor nutrition in Native communities. Similarly, the Wisconsin Oneida nation has worked to reintroduce Three Sisters agriculture, the ancient symbiotic agricultural system that permitted Oneida people to produce abundant harvests of sacred White Corn to sustain their people through the centuries without pesticides and without exhausting the nutrients of the soil. Oneida efforts involve the preservation of heirloom White Corn seed, but also include educational programs on Three Sisters growing techniques in order to repatriate this agricultural knowledge, Tsyunhehkwa, as described on the Oneida tribal website HERE. Recipes for dishes like corn bread can be shared as a way of reintroducing nourishing foods into tribal diets. You can read about such repatriation efforts in an interesting article in the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel HERE. Along with acts of repatriation, Wisconsin tribes have undertaken interventions to reclaim and reshape history in ways that reflect Native perspectives. On the Lac du Flambeau reservation, the tribe was faced with a vexing issue in trying to decide what to do with the surviving buildings of the Lac du Flambeau boarding school, one of the many Indian Boarding Schools discussed in the South Quadrant of this website. After careful deliberation and consultation with tribal elders, the tribe decided to renovate the former boys' dormitory of the old school and use it as the office for the tribe's language revitalization program. In this way, a building that long symbolized the systematic destruction of Ojibwe language and culture becomes refigured as a vehicle for recovering Ojibwe language for future generations.

The old boys' dormitory, being converted into a language center.

A stormy episode occurred in Wisconsin history when Ojibwe chose to exercise their right to practice spring spear fishing of walleye in lakes outside of their reservations. Although the right to fish, hunt, and gather was specifically and repeatedly guaranteed in federal treaties as detailed in the East Quadrant of this website, the state of Wisconsin sought to block Ojibwe practice of these traditions outside of tribal lands. The George W. Brown, Jr. Ojibwe Museum and Cultural Center in downtown Lac du Flambeau includes artifacts and displays from this important conflict, which represented an assertion of Ojibwe sovereignty. Work for the recognition of tribal rights to the benefits secured by federal treaties is an area of ongoing activism for many Indian nations today, and can be seen as a further example of the process of decolonizing Native American societies and the wider society of the United States. Some Images of the Lac du Flambeau Reservation

Lac du Flambeau Tribe: http://www.ldftribe.com/ According to the Lac du Flambeau tribal website, the area of the reservation today comprises some 44,957 acres of timber land, 260 lakes, 65 miles of streams, lakes and rivers, and 24,000 acres of wetlands. The area was established as a reservation through federal treaties signed in 1837 and 1842.

Downtown buildings in Lac du Flambeau show the variety of institutions and services maintained by the tribe today. (TD)

The George W. Brown, Jr. Ojibwe Museum and Cultural Center, in downtown Lac du Flambeau, offers a nuanced look at Ojibwe life, past and present. (TD)

The museum's architecture and decor signal a distinctly Ojibwe approach to the museum. (TD)

Displays within the museum illustrate aspects of traditional Ojibwe life in relation to the four seasons. (TD)

Displays also highlight the sometimes negative relations between the tribe and its white neighbors. (TD)

A number of items on display chronicle the twentieth-century conflict between Ojibwe and other Wisconsin residents regarding the practice of spear fishing. (TD)

The museum's collection also includes exemplars of past birchbark canoes, which are wonderful to examine and compare with more modern renditions, such as the canoe now on display at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. (TD) Lac du Flambeau is also home to the Woodland Indian Art Center, a remarkable resource for Ojibwe art. The center sells locally produced art and also runs an online shop.

Nesper, Larry. 2002. The Walleye War: The Struggle for Ojibwe Spearfishing and Treaty Rights. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press. Peterson, Diana L. 2005. Three Sisters Gardening: Rejuvenating a Traditional Food System with the Oneida Tribe of Indians of Wisconsin. MS thesis in Environmental Science and Policy, University of Wisconsin-Green Bay. Ridington, Robin and Dennis Hastings (In'aska). 1997. Blessing for a Long Time: The Sacred Pole of the Omaha Tribe. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press. Vizenor, Gerald. 1999. Manifest Manners: Narratives on Postindian Survivance. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press. Vizenor, Gerald. 2009. Natural Reason and Cultural Survivance. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press.

|